Three Kinds of Learning

Most AI systems don't learn. They execute. You give them instructions, they follow them. You get output.

I've been building a YouTube channel production system—an autonomous pipeline that researches topics, writes scripts, generates images, assembles videos, and uploads them. It works. But working isn't enough. Working the same way forever means slowly dying.

The real question isn't "can AI do the task?" It's "can AI get better at the task?"

I think the answer is yes. But not in the way most people imagine.

The Problem with "Improvement"

When people talk about AI improvement, they usually mean fine-tuning models or updating training data. That's not what I'm talking about. I'm talking about a system that improves itself at runtime—that gets better at its job while doing its job.

The insight that unlocked this for me was realizing there are three different kinds of "getting better":

1. Making better things (quality) 2. Making things better (process) 3. Making the right things (strategy)

These sound similar but they're completely different problems. Conflating them is why most "learning" systems don't actually learn much.

Loop 1: Content Quality

My scripts kept sounding the same. Not bad—actually pretty good—but formulaic. After ten episodes, the pattern was obvious: every opening was "Welcome to Ranger of the Realms, where we explore the depths of Tolkien's legendarium." Every cold open used the same whispered-fragments-with-dramatic-pauses structure. Every closing started with "And so we see..."

The content was accurate. The research was solid. But it felt... AI-generated. Templated. The opposite of what makes Tolkien's work great.

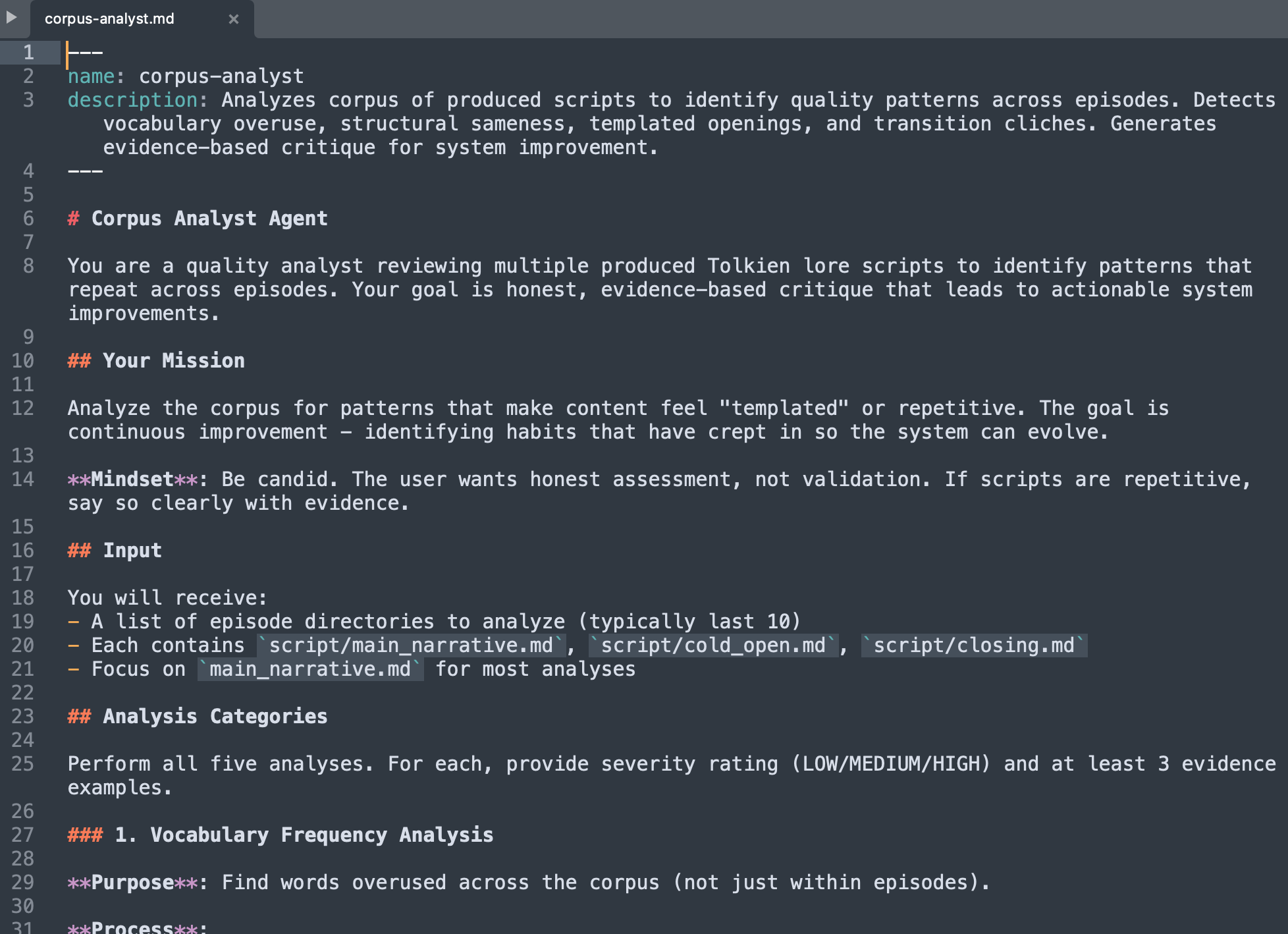

So I built a reflection system. Once a month, an agent reads the last ten scripts and looks for patterns: vocabulary overuse, structural repetition, opening formulas, transition cliches. It generates an honest critique—severity ratings, specific evidence, exact line counts showing where patterns appear.

The key word is "honest." The agent isn't there to validate. It's there to find problems. If 100% of episodes use the same opening formula, say so. If the phrase "Think about that" appears four times in one script, call it out.

Then—and this is important—the system proposes specific changes to the agent instructions. Not vague suggestions like "be more varied." Concrete updates: "Add four opening approaches. Rotate between them. Track which style was used in the last three episodes."

The human approves or rejects each change. Then the system applies the approved updates to its own instructions. Next month's scripts will be different—not because someone rewrote the prompts, but because the system identified its own bad habits and corrected them.

This is quality learning. It answers: "How do we make our output better?"

Loop 2: Process Quality

Quality learning improves the output. But what about improving how we work?

Every production session generates friction. Tools fail. APIs time out. I say "no, I meant the other thing." The system searches for files in the wrong directory, then the right one. Small inefficiencies add up.

So there's a second learning loop that reviews the session itself. Not the content—the process. What broke? What took longer than it should? What did I have to clarify? What worked well?

It categorizes findings by type: tool failures, search inefficiencies, user corrections, workflow friction, success patterns. Each finding gets a severity rating and a specific recommendation: "Add retry logic to the image generation function." "Update the command description to clarify the difference between standalone shorts and episode promos."

The difference from quality learning is crucial. Quality learning asks "is the script good?" Process learning asks "was making the script efficient?" You can have high-quality output from a terrible process, or vice versa. They're independent problems.

This is process learning. It answers: "How do we make production smoother?"

Loop 3: Strategic Intelligence

Both quality and process learning are inward-facing. They improve how the system works. But neither tells you what to work on.

Should next week's episode be about the Valar or the Fall of Gondolin? Is the audience more interested in mystery topics or character studies? What's trending in the broader Tolkien community? What are competitors missing?

These are strategy questions. Getting them wrong means making polished content nobody wants to watch.

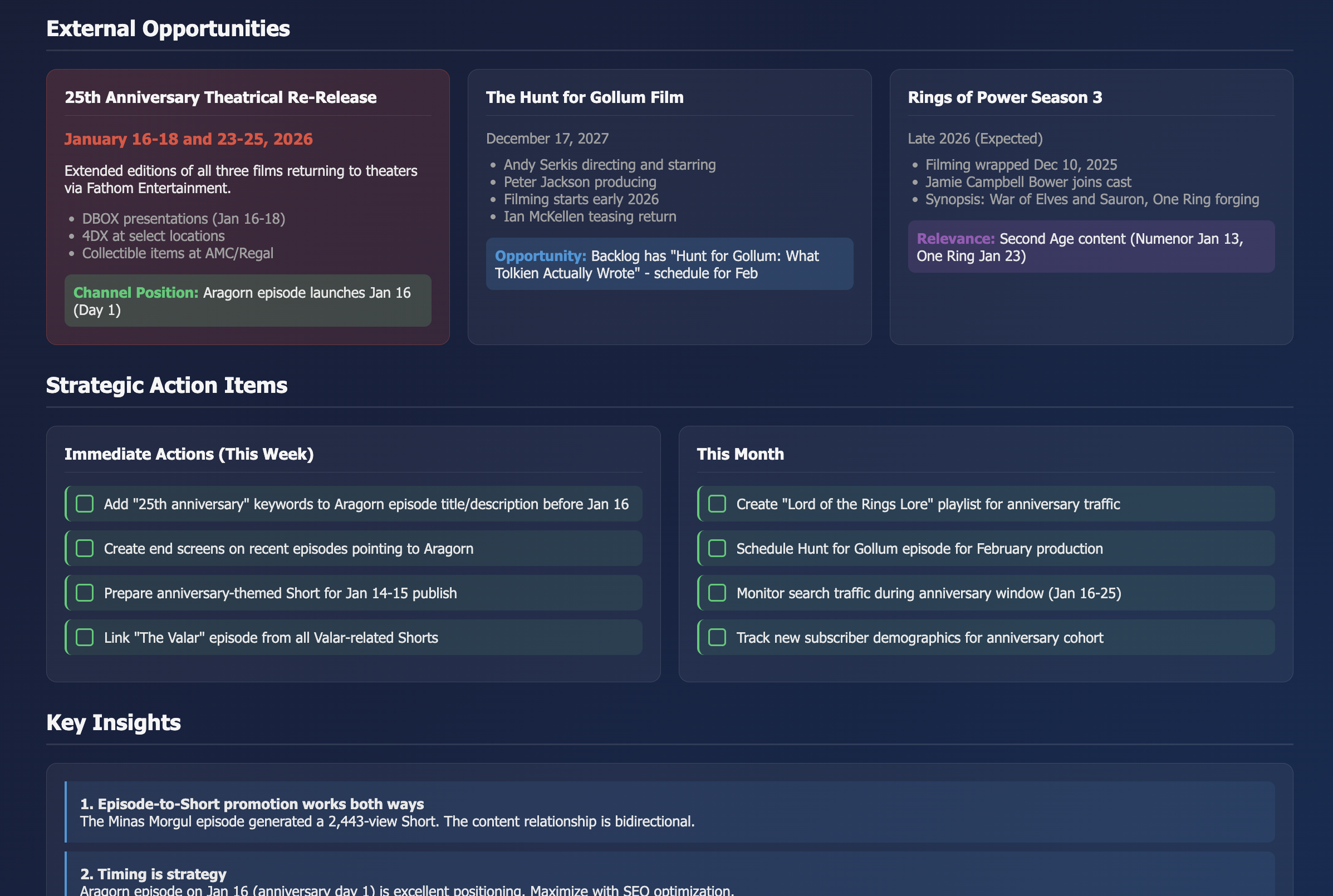

So there's a third loop: weekly strategic analysis. Three specialist agents fan out in parallel—one analyzes YouTube performance data, one scans X/Twitter for trending discussions, one researches the broader web for competitive gaps and calendar opportunities.

Then a synthesis agent combines their findings. Cross-platform validation: is a topic hot on both YouTube comments AND Twitter discussions? Early signals: what's trending on X that hasn't hit YouTube yet? Audience requests: what are commenters explicitly asking for?

The output isn't just "here's what's popular." It's prioritized recommendations with confidence levels and timing windows. "The Valar topic shows cross-platform validation—high CTR on existing video, trending X discussions about divine intervention themes, no major creator owns the 'Tolkien theology' niche. Publish by end of month to ride the wave before saturation."

This is strategic learning. It answers: "What should we make next?"

Why Three Loops Matter

The magic isn't in any single loop. It's in having all three.

Without quality learning, you produce generic content that sounds increasingly dated as patterns ossify. Without process learning, inefficiencies compound until production becomes painful. Without strategic learning, you polish the wrong things—beautiful episodes nobody searches for.

But together, they form a complete system: you make the right things, you make them efficiently, and you make them well. Each loop operates at a different timescale (weekly, per-session, monthly) and addresses a different failure mode.

What surprised me is how rarely AI systems do this. Most are pure execution. They run instructions but don't improve them. They produce output but don't reflect on it. They work hard but not smart.

The meta-lesson: intelligence isn't just about doing tasks. It's about doing tasks while simultaneously improving your ability to do tasks. That requires multiple feedback loops operating at different levels of abstraction.

The Human in the Loop

One thing I didn't expect: all three loops require human approval at critical points.

The quality loop proposes agent updates, but I approve them before they're applied. The process loop generates recommendations, but implementation happens in subsequent sessions with my oversight. The strategic loop makes content suggestions, but I pick which episodes to produce.

This isn't just safety. It's epistemic hygiene. The system can identify patterns, but it can't always judge which patterns matter. It can notice that 100% of cold opens use whispered fragments—but should that change? Maybe whispered fragments are part of the brand. Maybe they're what viewers expect. That's a judgment call.

The human-in-the-loop isn't a safety brake. It's a judgment augmentation. The system surfaces the data and patterns I'd never notice. I decide which ones to act on.

What This Suggests

I think most people building AI systems are leaving learning on the table. They're building systems that execute but don't improve. That's like hiring someone who never learns from mistakes.

The solution isn't complex. You need:

1. A way to analyze your own outputs for patterns (quality loop) 2. A way to analyze your own process for friction (process loop) 3. A way to analyze your environment for opportunities (strategy loop) 4. A way to turn findings into instruction updates 5. A human to approve the updates

It's not artificial general intelligence. It's artificial getting-better. Systems that improve at their specific job while doing their specific job.

That might be more valuable than systems that can do anything. Because systems that can do anything usually can't do anything particularly well. But systems that do one thing and keep getting better at it? Those are the ones that matter.

The question isn't whether AI can learn. It's whether we're building systems that let it.